I was discussing a case with a colleague and thinking out loud about why Blood stasis can be part of an anxiety presentation. Here are some thoughts about the deeper “Why” of moving Blood.

Blood – the Ying level – is about the present moment, the consciousness, the Primary channels, it’s what the Zangfu are doing right now.

When all is well, the Zangfu serve the present moment. There’s no detritus from the past, and no pressing “pause” on the present moment to dwell in a fantasised future. The consciousness senses the external world and, in a way, flows through the external world via sense perceptions. The energy of the external world – it’s vibrations of sound, light etc, flow through into the interior, meeting no impediment, touching the pure Spirit. There is a state of harmony between interior and exterior.

The body is a vessel for this harmonious flow. Whatever it needs is communicated via hunger, cold etc. When needs are met there are feelings of pleasure and a completion of the cycle of desire. This is the Zangfu serving the vessel to peacefully coexist within the present moment.

The present moment is the only state that exists – past and future are just imprints on the Blood (or deeper impressions on the foundation of Yuan Qi), creating memories and fantasies respectively.

From a Daoist perspective, the whole is perfect. The cosmos is perfect. It’s an unceasing flow of perfection and benevolence. When we become more and more fluid, we can accept the outer circumstances with more and more equanimity.

“This is the essence of Tao.

Stay in harmony with this ancient presence,

and you will know the fullness of each present moment.”Lao Tzu

(trans. Timothy Freke, 1995)

When we help a person by nourishing Blood and moving stasis, we allow them to experience the perfection of the Dao.

So how does a person come to be outside of the experience of perfection?

Stasis happens in any moment when the vessel isn’t equipped to let the energy of the world in. Maybe the configuration of Yuan Qi at birth resulted in obstacles. Maybe something from the exterior was too overwhelming such as physical trauma or abuse. So the body creates stasis in the Luo vessels to siphon that vibration from the present moment, attaching it to the Yin medium of Blood, like locking it, freezing it. Using the Yin-stillness of Blood to contain the Yang-movement that could cause disarray.

As these locked places multiply, now when the world’s vibrations come to flow into this person, there are blocks and obstacles and the message doesn’t arrive well in their Centre. The person doesn’t perceive Dao’s perfection and doesn’t experience the world with harmony or equanimity. It’s as though members of an orchestra are sitting in different valleys – they all strike a note at the same time, but the waves of sound don’t harmonise and resonate together. There are interference waves, no matter which hill or dale you visit. Even though the music itself is beautiful, it can’t be perceived as such.

If the perception of the Dao is obstructed, then there can be a deep sense of “wrongness” about the world and a person’s position in it. Feeling unsafe and not held, feeling a sense of not belonging, jumpy because perceptions are not arriving harmoniously, temporarily creating a false sense of connection by worrying about things… these are manifestations of a blocked relationship of the exterior coming in. There may also be hopelessness, frustration, lack of clarity, lack of meaning or fear around the expression of the Spirit into the world, from the interior moving outward.

As Sean Tuten says, we ALL are walking around with Luo vessels, all the time (unless we are enlightened Daoist masters!). Life is challenging and we create Luos to protect the purity in the Centre, to protect the sacred.

If we have experienced challenges and hardship, then what’s stuck in our bodies is simply the wrapping paper of those experiences. We have already received the gift of growth, empathy, compassion, self-awareness, strength, determination, wisdom… we can toss out the wrapping paper without fear of losing those gifts.

Our role as practitioners is twofold:

1. Keep ourselves as fluid as possible, so that we may naturally carry out our sacred function in the world

2. Help our patients to become as fluid as possible, so that they may naturally carry out their sacred function in the world

Nourishing and moving Blood helps us, and our patients, to become full with this moment and to release the debris of the past.

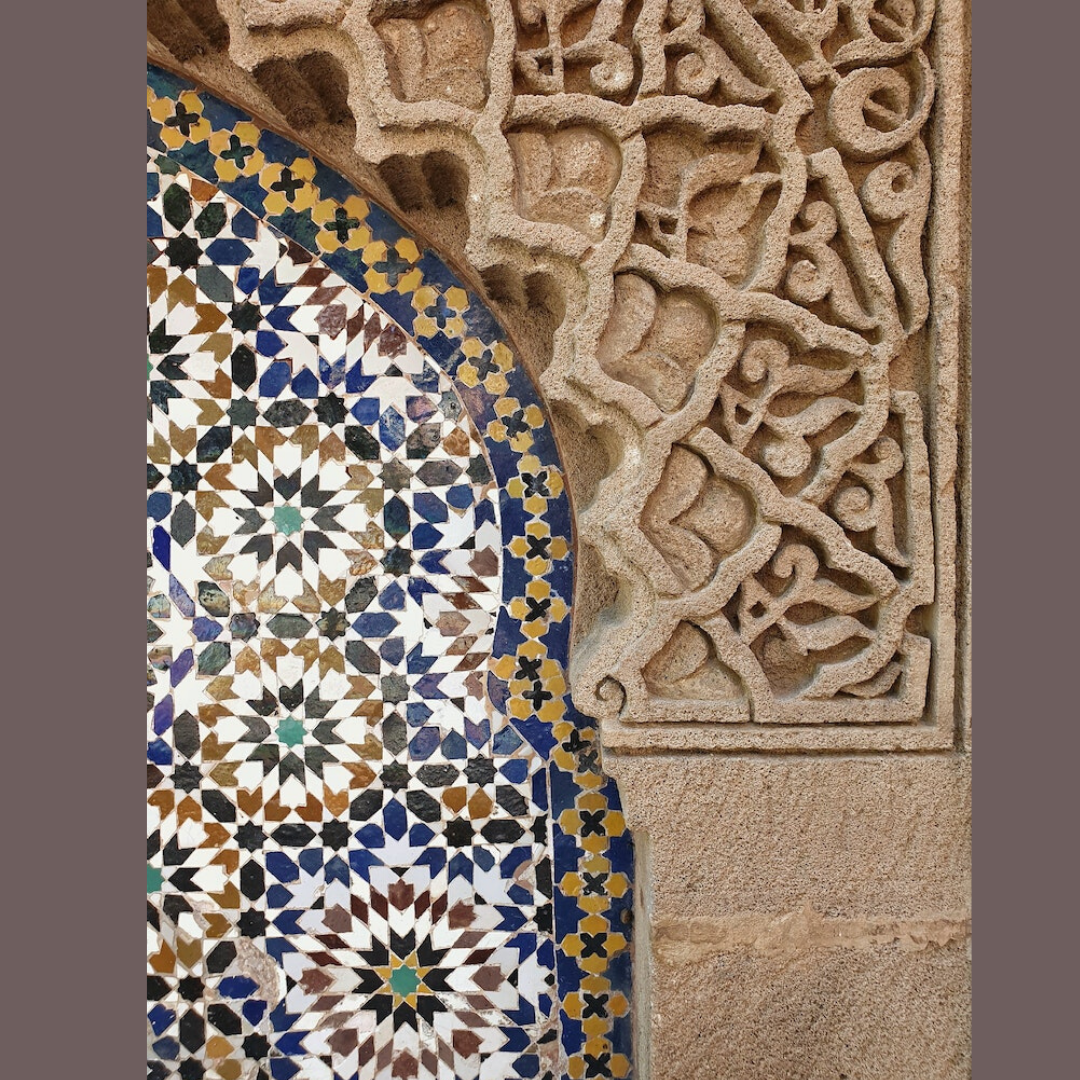

Image thanks to Hitanshu Patel on Unsplash