Everyone has spirituality.

That’s not the same as saying everyone is religious.

But everyone has a set of beliefs – deep guiding principles – that create their foundation of what they feel life is all about. These beliefs also lead to a person’s expectations of what happens to the mind after death, their own sense of life purpose, their opinions about things in the world that appear to be good or evil… even if the person says that they don’t have any beliefs whatsoever, it’s actually not possible for a human being to take a neutral stance.

Does this matter for Chinese medicine practice?

It depends on what kind of practitioner you are. But I’m guessing that if you’re on this site, reading this post, that it probably does matter to you – in some way.

Maybe you’re quite agnostic yourself, but you’re empathic and caring too. Your patients may be grappling with life’s big issues, and drawing on their spiritual or religious frameworks to make sense of things. Maybe you’d like to create space in the treatment room for this exploration, but aren’t too sure about how to do this in a way that’s safe and appropriate for both patient and practitioner.

Maybe your spiritual practice is extremely important to you, and serves as your guiding light through life, in good times and bad. You can feel how deeply this impacts your sense of wellbeing on many levels. Maybe you would love to be able to share this level of wellbeing with your patients, but can’t imagine how to do so without using language that could alientate or offend.

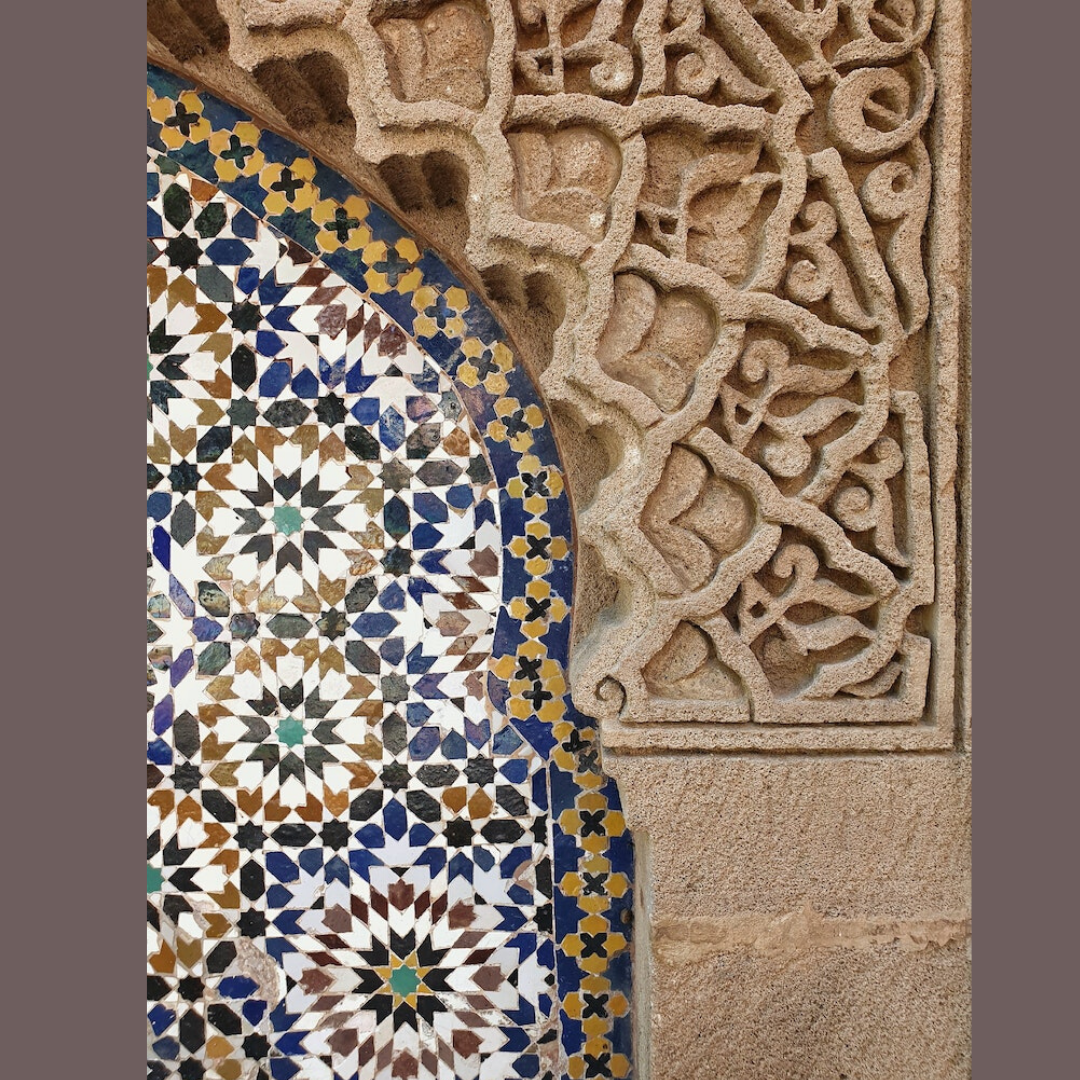

I’ve been interested in the human expression of spirituality for many years. I’m fascinated by the rich diversity of symbols, traditions and meaning-making. And within this diversity, I’m struck by the core themes that recur throughout time and across cultures. These are core themes within teachings and practices that seem to simply make humans feel and act in a more contented and harmonious fashion.

I started practising Chinese medicine right after handing in my psychology dissertation. My dissertation was on the language used by non-religious people to express what they defined as their personal spiritual experience. That was an amazing exploration.

Then I opened my Chinese medicine practice and spent my days in the treatment room with people describing their life’s journey, their struggles and their celebrations.

For many years I felt this invisible barrier that prevented me from being able to hold space for appropriate conversations that really touched into a person’s deeper sense of themselves, and their reasons for being here. Somehow, even though the standardised Chinese medicine that I’d learnt at university included things like emotions and so on, it was still, in hindsight, quite a medicalised model of human experience.

It wasn’t until I started exploring what can be called Classical Chinese Medicine, starting with Dr Yaron Seidman’s Hunyuan Medicine, that I began to develop a clinically-relevant language of embodied, natural spirituality.

This theme of embodiment had surprised me when it emerged in my interview-based thesis research. Most of the research participants talked about physical sensations when describing their unique spiritual experiences, and used phrases like knowing things “in their bones” to describe a sense of absolute certainty. There was a sense that they were not being influenced by external ideas, but rather it was something personal and sure because they could feel it.

And within these very personal experiences was the admission of a sense of wonder and mystery. It took some time to journey with people to that place of innocence. Many of the participants had built up a fairly thick skin around their tender, unique ideas of life and the universe – but given the time and the space, they softened into their own story. And once they understood that I respected their intellectual stance and reasons for choosing their own personal philosophy, then they allowed me to share their innocent sense of wonder at life and its sometimes mysterious strangeness.

Our culture has a lot of language for the Yang aspect – the visible. And Chinese medical philosophy has a rich treasure trove of symbols, metaphors and analogies for the hidden aspect of everyday life. Yin. Mysterious. Hidden, yeilding. Dense, stopping. Dark, feminine. The interplay of Yin and Yang being life itself, this language of Yin and how we directly experience it through the physical body, in our ordinary daily movements, is often a revelation for our patients.

Yin is life’s mysterious beauty, hiding in plain sight.

Once a patient has an embodied, everyday understanding of the mystery that is an essential part of their nature, with an appreciation of the cycles of life and ancestry that create their present experience, they can’t help but to open up effortlessly into their own, personal, real, embodied spiritual truth. In their own way. At their own pace.

This exploration has deepened further with my experience in Jeffrey Yuen’s lineage. With acupuncture as the starting place, as taught by Ann Cecil-Sterman and Sean Tuten, the description of the channels, the body’s creation story, the epic myth of self in the world that is our life’s curriculum – all of these deep ideas are woven into discussions of runny noses and period pain.

It is seamless, because it’s Chinese medicine.

Image credit:

Mustafa Elkhnati